The last time company came for the weekend, I did the requisite tidying of guest rooms— making sure to dress the beds with clean sheets, sweep and mop the floors, and straighten the stacks of books and food-related zines into neat and interesting piles. Preparing for guests, this time two baker friends, also means doing our best to contain the flotsam and jetsam that overtakes the spare bedrooms–– stacks of boxes for shipping shrub, overflowing bins of seed packets and tiny gram bags of self-saved seed, pie packaging, produce packaging and the carnival of food projects stuffed in the dank corners of each room. On this most recent occasion, one room smelled overwhelmingly of vinegar, so I followed my nose to the suspected five-gallon bucket where I found a colony of fruit flies gathered in holy congregation on the wall above the bucket. The guilty vinegar project had bubbled actively toward its porous cloth cover and soaked it well enough to advertise its contents to the fruit flies. To them, it was an intoxicating neon sign.

“Jamieeeeeee!” I yelled.

When people visit our home, we tell them “this is a working household” to preface the benevolent chaos that awaits inside, where the fruits of the field and its excesses make their way into the kitchen and subsequently, all usable corners of the house. I’m sorry to report, but this is our singular design aesthetic.

Like any good country home, we welcome people through the side door. Folks must bypass the duo of beat up plastic buckets where old salad dregs, peach pits, egg shells, and spent lemons exit the bakery and home kitchen, awaiting their journey to the compost heap. Along the wooden railing are used dish towels hung to dry before being thrown into the wash pile. A plastic green harvest bucket of brassy pears pulled from a nearby tree perches there too. Stacks of empty produce boxes sit opposite the door, remnants of the big tomato pie bake we completed the other week and the peach galette bonanza the week before. All will be hauled to the dump and recycling center, a common chore in rural places where municipal services don’t oblige freely.

Opposite the tower of boxes are mud boots, muck boots, and boot boots caked with red clay. You’d assume we take our shoes off upon entry, but we don’t. Not for lack of wanting to, but because it’s impractical in a home that doubles as a workplace for at least seven people any given week. Above the threshold, a plastic gallon bag filled with water and two pennies hangs precariously overhead to “ward off” the flies. My husband swears by this zip-locked lore, but judging by the amount of fly murders I’ve committed this summer, I’m not so sure. All that, and I’m afraid you’ve only just made the approach to our front door, lol.

Our working household encompasses the breadth of our food work: the whims, the obligations, the projects, and the inevitable failures. I’d like to think making use of the harvest is at least a part of every small farmer’s job description; as in, someone has to use up the ugly tomatoes, bruised eggplant, and bumper crops of squash and zucchini. Rural and indigenous communities, and those growing for sustenance, have for centuries engaged in food preservation as a means of ensuring longevity for the hard-earned harvest. It also meant survival in lean times.

In our home, it’s a mixture of both. We want to value the food we grow sincerely and use it for sustenance. I suspect my husband’s inclinations for preservation lie somewhere between his culinary curiosities (he was a chef for two decades before moving back to the family farm) and his down-home thriftiness. Finding a deal, a steal, or avoiding paying the full price of a thing (anything!) is damn near a commandment to him. Transforming food or food waste is sacred practice that taps into his most innate sensibilities and the family practices handed down to him. Jamie’s family canned, pickled, and jammed their way across generations. Putting up was a necessary way of life.

My own kitchen sensibilities grew more out of a desire for a domestic usefulness, and maybe even to become something like what the writer Laurie Colwin calls a “domestic sensualist.” I didn’t grow up with a practice of food preservation, but when I moved to North Carolina over a decade ago and followed my curiosity for all things food-related, it was a skill I decided was worth having. I find beauty within processes, which is why baking appeals to me. I am fascinated by the act of converting fresh food or wild things from one state of being to another. Whether dehydrating fig leaves into powder or cooking a pot of macerated plums into ruby red jam, the joy is in the sensory details– the smells, the sounds, the colors, the transformation!

Once a person sets foot in our home they are quickly dumped into the bakery, which before it was a bakery was a strange ancillary space that was neither dining room nor living room; something Jamie proclaimed, “The Production Kitchen!” when he first saw it. Nowadays, there is a wooden baking table, professional oven, low-boy fridge and standing freezer, metro racks, speed racks and flour bins.

In this season, as summer wanes and the sunlight recedes, last gasp tomatoes line the metal shelf beneath the big mixer––a large basket of Cherokee purple cherry tomatoes and another with green tomatoes for pickling. More than once, as is the case in this working household, the green tomatoes sit long enough to turn red, bypassed by other more urgent summer tasks. We might very well roast them or make salsa, but some years they blemish and fester, seeping onto the floor, inviting the fruit flies to feast.

The house is one large galley, so the bakery space gives way to our actual kitchen, gives way to the dining room, and ends in a colorful bookshelf containing our culinary library.

Though my husband has the bulk of his kitchen projects stowed in sneaky corners all over the house, I have my own mess. Just over the border of the bakery, where the laminate floor turns to linoleum (a relic of the previous owner), there is a corner completely overtaken by foodstuffs, mostly quarts of damson plum jam and random one-offs– tomato, last year’s cranberry-satsuma, and a small run of raspberry from the farmer who faithfully texts every time he picks a quart. A bread basket overflows with spent vanilla beans waiting to be plopped into the next bubbling pot of fruit and sugar. Wine buckets stuffed with whisks and wooden spoons, potato mashers and ladles— the only relatively contained part of the chaos. Otherwise, the tiny corner is strewn with deli containers of corn husk powder and fennel pollen, bags of dried marigold and calendula leaves, and bottles of half-used vinegars to be poured into handpie fillings.

Our home kitchen island is never without a few jars of pickles– pickled okra, a gift of pickled green tomatoes, and hot pickled peppers ready to accompany the next meal. This time of year, a bowl of freshly gathered chestnuts occupies a small bowl. Don’t open the pantry unless you want to enter the Narnia portal of preserved foods, jars of all sizes labeled years back, yet some with no label at all, sealed in utter mystery. Bags of dried chiles clamor over each other in the uppermost shelf awaiting to be turned into spices and flavor-boosting powders like the jars of burnt allium powder and Nora paprika below.

The pantry being a portal of possibility, things get more troublesome in the guest bedrooms, where Jamie likes to store his five-gallon bucket-sized projects, usually vinegars and vegetable ferments. Bedroom one harbors buckets of fermented lime and plum vinegar from 2021 (eek!), and ferments of habanada peppers and fish peppers started November of last year. These buckets I refuse to open lest a Candyman-esque horror scene emerge. Ask me how I know.

Beneath a handmade comal, gifted to us by a potter pal, is the 2024 “ACV” project filled with apple peels and cores left to transform in a bath of apple cider for the year. The wild yeast on the apple scraps will feast on the cider’s sugars, before turning to alcohol and eventually, true apple cider vinegar. On the window sill is a glass jar filled with pine cones and brown sugar, a new project Jamie says will turn into pine syrup in a year’s time.

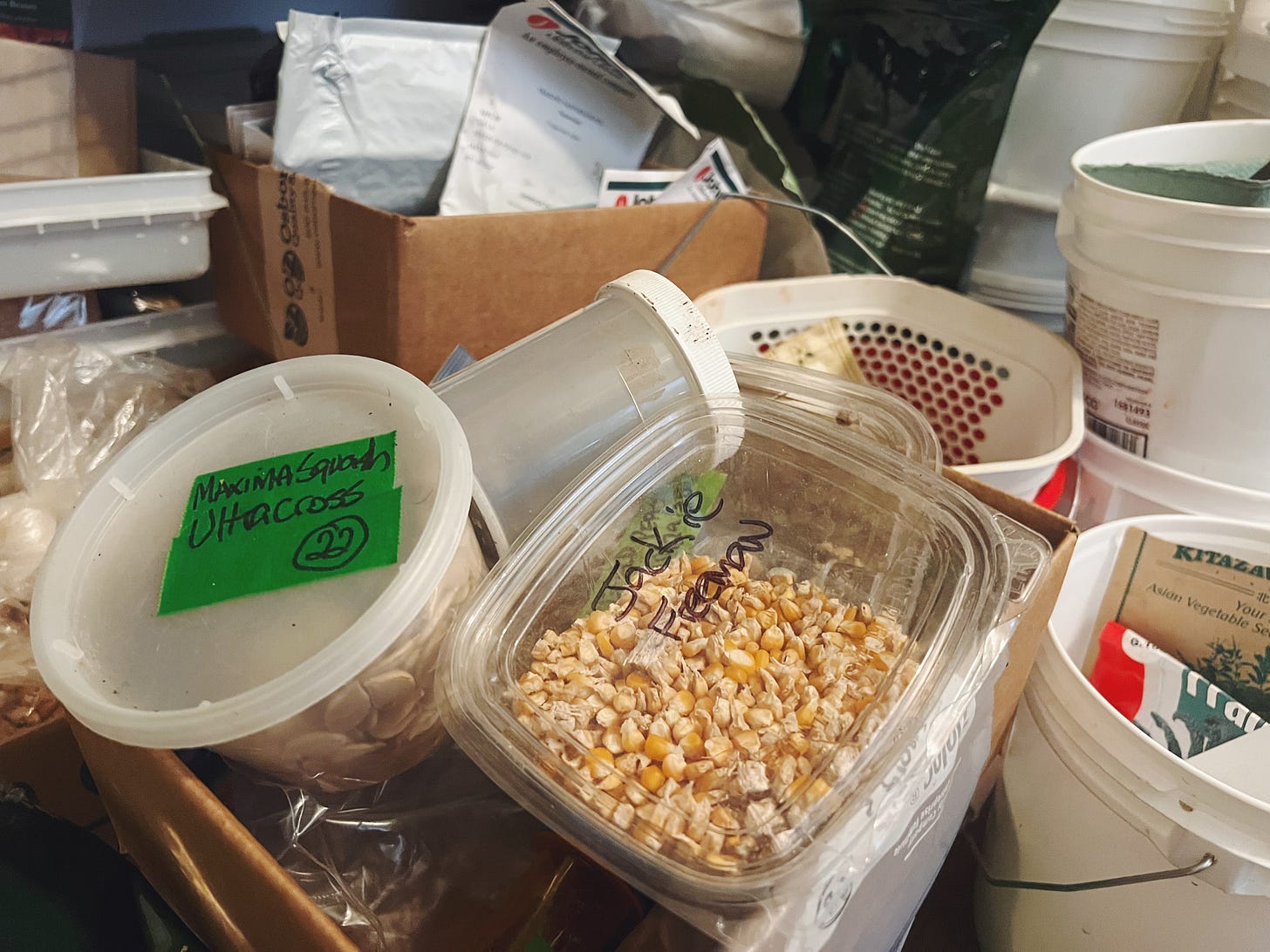

The second guest bedroom houses more projects including a 22-quart container of lacto-fermented corn with small “Long John Silver-style” cobs getting funky in their salt brine. Next to that, a smaller bucket labeled “Banana Bio” holds a homemade soil amendment using banana peels from the bakery’s weekly banana bread production. A similar closed-loop situation happens with the bakery’s egg shells, which get roasted and buzzed into a calcium-rich amendment. On the bench at the foot of the guest bed, quart jars filled with watermelon rind pickles made during the height of summer nest inside cardboard boxes. Scattered about are sheet trays of seed heads pulled from flowers in the garden, and sixth pans of winnowed seed. Between the actual furniture in this room, the bookshelf and thrifted mid-century dresser, are hand-carved birdhouses to be placed in future pollinator gardens and plastic trays of haphazardly stowed silverware for farm events.

The good thing is that most of the folks who pass through our home are some combination of food and farm person, just like us. At least one time per visit we’ll inevitably pull the vinegar and hot sauce projects from their hiding places and offer them up to taste. The funhouse of food and farm projects, the beautiful mess, usually stokes interest rather than aversion. It begs occasion to share and exchange knowledge and perhaps inspire curiosity. What we lack in Instagrammable home design and bespoke aesthetics, we make up in warmth and care and plenty of food.

A recent visit to the home of another farm friend offered comforting affirmation. Their house smelled of a recent pawpaw harvest from their lush orchard. As I entered their home, boxes of the native fruit were packaged and resting on shelves near the front door. Large stock pots sat opposite the three-well sink of their home kitchen. A cast iron pan sizzled with the gift of lunch and a familiar dance ensued between my farmer friend and her shepherd husband. A working household is never fancy, but is always rich with a genuine hospitality.

We tell people, “this is a working household,” and you are always welcome here.

😍🫶😍🫶😍 yesss this is so familiar and so beautifully presented!

beautiful and hilarious 😝 I know it all too well. xo